I fancy myself an environmentalist. I recycle, backyard compost, have rooftop solar, rarely use AC or heat, drive a hybrid, don’t have a lawn and eat vegetarian.

Yet the truth is I am as responsible for climate change as the next guy. Here’s why.

Doing those things makes me feel good about myself, but they don’t move the world measurably closer to solving the climate crisis. My journey to this conclusion began by looking into my personal carbon footprint using readily available online tools.

The U.S. EPA’s carbon footprint calculator, for example, looks at three sources of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions: home utilities for heating, cooling and cooking; vehicle fuel efficiency and miles driven; and non-recycled waste generation. In these areas, my carbon footprint was roughly half that of other people living in my zip code.

However, roughly two-thirds of Americans’ GHG emissions are embedded in so-called “indirect” emissions released during the production of all the other things we consume, such as food, household supplies, apparel, air travel, and services of all types, according to an in-depth analysis by the Center for Global Development, a non-profit policy research organization.

However, roughly two-thirds of Americans’ GHG emissions are embedded in so-called “indirect” emissions released during the production of all the other things we consume, such as food, household supplies, apparel, air travel, and services of all types, according to an in-depth analysis by the Center for Global Development, a non-profit policy research organization.

Furthermore, higher income suburbanites like me generally consume more goods and services, which ratchets up their carbon footprint compared to people in lower income brackets.

Despite my efforts to live “green,” my lifestyle is highly energy intensive, as is that of the average American who is responsible for GHG emissions equivalent to dumping 21.8 tons of CO2 into the atmosphere annually, according to the Center for Global Development’s analysis.

I then looked into the energy input it takes to support the typical American lifestyle which drives the burning of fossil fuels and climate change. Luckily, Professor of Physics Richard Wolfson of Middlebury College has an ingenious demonstration that does just that.

A hand crank is set up to drive an electric generator connected to 100-watt lightbulbs. A typical person can turn the crank fast enough to keep one lightbulb lit, but not two. Thus, the work output of a human body is roughly equivalent to 100 watts. Wolfson designates this 100-watt energy output as one energy servant. The question then is, “how many energy servants does it take to support the average American lifestyle?”

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, U.S. energy consumption in 2016 totaled 97.4 quadrillion Btus (British thermal units). Converting to familiar units and to a per capita basis averaged around the clock, the typical American lifestyle consumes energy at a rate of roughly 10 kW (kW=1000 watts), which is equivalent to having a staggering 100 personal energy servants cranking away non-stop, 24/7.

This humbling exercise led to an inevitable conclusion. My feel-good actions to decrease my carbon footprint don’t amount to a drop in the bucket. Solving the climate crisis is going to require either wholesale chucking of the American lifestyle or a nationwide collective shift from a fossil fuel to a sustainable energy economy. Given that returning to horse drawn carriages and pony express mail is beyond unrealistic, the path forward crystal clear.

This humbling exercise led to an inevitable conclusion. My feel-good actions to decrease my carbon footprint don’t amount to a drop in the bucket. Solving the climate crisis is going to require either wholesale chucking of the American lifestyle or a nationwide collective shift from a fossil fuel to a sustainable energy economy. Given that returning to horse drawn carriages and pony express mail is beyond unrealistic, the path forward crystal clear.

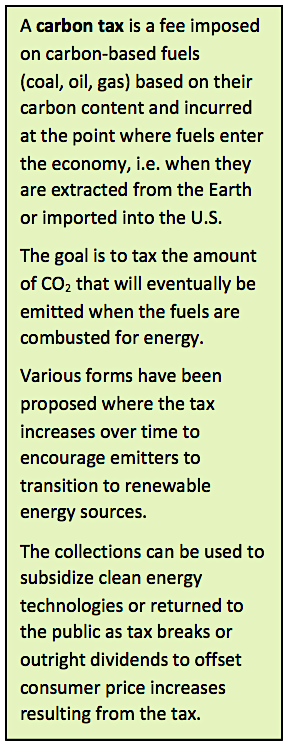

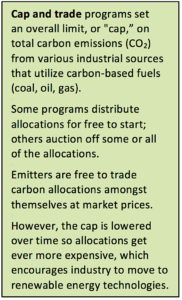

Collective action at the federal level is imperative. There are only two legislative solutions on the table, a carbon tax and cap-and-trade (see sidebars for definitions). It is incumbent upon us all, as citizens, to familiarize ourselves with both and to pressure our representatives in Washington to speedily enact a national legislative fix.

Even conservative economists widely view a simple carbon tax as the most workable solution at the federal level to transitioning to clean energy: It’s less costly than other approaches which conservatives tend to oppose, like regulations, subsidies and mandates, and can be easily adopted by other countries.

The most important contribution of personal actions to decrease one’s carbon footprint is to set the psychological framework for wholehearted endorsement of collective action. Because of the enormity and urgency of the climate crisis, “walking the talk” as an environmentalist means going beyond personal behaviors to promoting collective action.

***************************************************************************

Sarah “Steve” Mosko is a psychologist, sleep medicine specialist and freelance writer focused on environmental issues. Visit http://www.boogiegreen.com/ to read other articles she’s published on current environmental problems and solutions.

Be the first to comment on "Collective action will solve climate crisis"