Tale of the Toppled Hurler: A Peter Hartwell Story

by Bruce A. Kauffman

c 2017 All rights reserved.

For full story to date, visit: https://escondidograpevine.com/a-the-tale-of-the-toppled-hurler-a-peter-hartwell-story/.

At last reckoning, another of Peter’s attempts to escape fails. Now the fat man is driving him south toward Braintree in the sleek Infiniti. The radio is on.

My host punched in the Opera Channel and sang along as we cruised toward Braintree, down Route 3, over the Sagamore Bridge and on into Hartsdale. The moon was dim behind a film of low clouds. We passed the landmark Donut Depot and the fat man pulled a hard left and then another and we were in the alley that ran behind the shop. He pulled into the tiny back parking lot and crunched to a stop on the gravel.

My host punched in the Opera Channel and sang along as we cruised toward Braintree, down Route 3, over the Sagamore Bridge and on into Hartsdale. The moon was dim behind a film of low clouds. We passed the landmark Donut Depot and the fat man pulled a hard left and then another and we were in the alley that ran behind the shop. He pulled into the tiny back parking lot and crunched to a stop on the gravel.

He pulled me out of the car and led me through a gray steel door into the Depot office. He left the door ajar and a briny breeze blew in. He pulled a string to turn on a lamp that hung low over a wooden desk with a light natural stain finish, and then he installed me in a hardback chair that faced the desk, wrapping me up like a mummy with a fresh raft of duct tape. He settled himself behind the desk in a wooden swivel chair with a slatted back.

“I don’t think I have to tell you that we’ve been keeping a pretty close eye on you lately,” he said.

He reached to his right and hit a button below the office radio’s amber screen. Harry Hardcore’s “Celestial Stream” came on, lulling me as usual into a calm state of acceptance. I clung to a thread of hope that there was a way out of this imbroglio and then just let the hope go. Somehow, giving up the feeling brought me back into the moment, and, grim as that moment might be, the tension left my body. “Celestial Stream” came to the chorus: “Slide Along The Milky Way With Those Among You With Whom You Are At Peace.”

He reached to his right and hit a button below the office radio’s amber screen. Harry Hardcore’s “Celestial Stream” came on, lulling me as usual into a calm state of acceptance. I clung to a thread of hope that there was a way out of this imbroglio and then just let the hope go. Somehow, giving up the feeling brought me back into the moment, and, grim as that moment might be, the tension left my body. “Celestial Stream” came to the chorus: “Slide Along The Milky Way With Those Among You With Whom You Are At Peace.”

The music was relaxing the fat man, too. His eyes fluttered and he laid his head down on the desk. His breathing became steady and rhythmic. His wheeze sounded fainter.

The long chord from Nipsy Sullivan’s Hammond B-3 signaled the piece was coming to a close. The B-3 pulsed, then faded into nothingness. Drummer Bobby Montefiore sounded the bell. After a minute or two, I surfaced, coming up slowly and gently. The fat man seemed to be staying deeply within his own reverie, his head resting on the top of the desk.

He remained still even when a trumpet blast sounded and a colonial-era town crier rang his own bell, calling out the time, 3:30 am., and that all was well. One item stood out. It was that a North Shore congregation would be dedicating a new community hall to the blessed memory of Samuel Saperstein.

When Sammy’s name came over the air, the fat man started huffing like a horse hustling down the stretch at the Belmont Stakes. I failed to catch the date and time over his noise. I figured it would have to be soon, plugged as it was here now on the radio. Even through the fat man’s loud breathing, I made out a mention of how the Sapersteins’ generosity extended even to the Cape, where Sammy and his wife had made a sizable contribution to the Willie Gillante youth center in Hartsdale, a fact which we had duly reported sometime ago in the News.

The fat man’s head bobbed up sharply. Though erect, he looked barely conscious, his eyes wide. Then his head fell with a thud back down on the desk.

It had come as a shock last Labor Day when we heard that Sammy Saperstein took a bullet point blank through the forehead in the middle of the afternoon while he dozed in an easy chair by the fireplace at his brother-in-law’s Cape house in West Barnstable. The wife and son had gone out shopping at the Hyannis mall.

Though West Barnstable is nearby, it’s not Hartsdale, so we had to reach for a way to fulfill our credos – “local angle, local angle, local angle” and “All Harstdale, all the time” — and yet latch on to some piece of this story so close by our border.

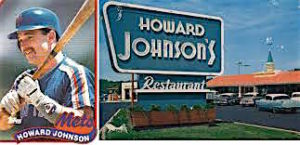

So Jimmy Clancy backed into a feature about how Saperstein’s Le Roi de Beignet chain had opened its first store on the Cape this past summer. The talk was the scaled-down store was a demonstration project for a network of cozy, boutique shops, perhaps one in Hartsdale. His son, heir apparent to the entire Le Roi chain, was honcho for the new project.

The daily Cape Cod Times out of Hyannis handled the brunt of the coverage: Apparent professional hit. Suicide ruled out. Crime of passion ruled out, too. No witnesses had come forward, and a neighborhood canvass came up empty. The wife and son had reportedly returned from their shopping trip with a big deep blue coffee mug with “World’s Greatest Guy” emblazoned thereupon in flowing yellow script, and found Sammy dead.

The daily Cape Cod Times out of Hyannis handled the brunt of the coverage: Apparent professional hit. Suicide ruled out. Crime of passion ruled out, too. No witnesses had come forward, and a neighborhood canvass came up empty. The wife and son had reportedly returned from their shopping trip with a big deep blue coffee mug with “World’s Greatest Guy” emblazoned thereupon in flowing yellow script, and found Sammy dead.

The Times’ obituary supplied this background: Samuel Morris Saperstein was born in Mattapan, Mass. on November 29, 1949, the son of immigrant Russian tailors who managed to stay a step ahead of Stalin after the war. Saperstein’s excellence in both athletics and academics at Boston Latin School earned him a full, four-year scholarship to Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, where he played lacrosse and studied economics, including a paid summer internship for credit with the Sara Lee bakeries.

In his junior year at Dartmouth, he met a sophomore from the University of New Hampshire named Judith Naomi Marks and they were married shortly after she was graduated. Three years later, they had a child, Sumner.

According to the Times, Sammy plunged all his savings into opening the first Le Roi de Beignet in Beverly Farms twenty-eight years ago. He persuaded his parents to buy shares, thereby making them rich.

Known for its high standards of cleanliness and purity, the company introduced the New Orleans-style beignet to eastern Massachusetts and grew to become Greater Boston’s first large-scale alternative to the traditional doughnut chains like Dunkies, formally known as Dunkin’ Donuts. The beignets were sprinkled with confectioner’s sugar and served with coffee with chicory.

A tabloid or two blew smoke about how Sammy must have led a double life, for why would such a prominent civic leader, a man known for his generosity to the community, be the target of such a crude execution.

The fat man raised his head off the desk. He turned his eyes toward mine and struggled to focus. “Fuckin’ Sammy,” he said, his tone affectionate. “I knew him. We grew up together at the tracks, playing those goddamned hounds. I miss the old Jew bastard.”

I heard the crunch of gravel and, through the open door, saw my Mustang pulling into the back lot. It wasn’t long before the car was swaying to and fro, Russell obviously occupied with Marie.

“So,” I said, “if you’ve quit the hit business, then there had to have been hits in the first place. Could we pass the time talking about them until Russell is done? Give us something to do? What does it matter what I know at this point? I’m about to go south anyway.”

“‘Them’?” the fat man said. “There’s only one. The only hit I carried out. It was many, many moons ago; many. Fellow by the name of Pietro ‘Plaid Petey’ Petrocino.”

“So, someone put out a contract on Petey for whatever reason, and you were lucky enough to get the job. You must have had a big payday on that one.”

“Kind of…” the fat man began.

“No others?” I said.

“There were no others,” he said.

“You ever stop by a place in Chatham?” I said.

“There are a lot of places in Chatham.”

“Coffee shops? Doughnuts?” I said.

“Oh no, you don’t,” the fat man warned me. “I had nothing to do with any hit on anyone called Fat Tony.”

I guess my memory had served. The hit was indeed in Chatham, where the fat man may have been linked to a doughnut shop and its owner by virtue of an attempted hostile takeover. Word at the time was Fat Tony was not about to sell.

“Fat Tony Antonio?” I said. “Also known as Jelly Donut?”

“We were amicable in our business relationship,” the fat man said.

“Let me guess,” I said. “You wanted it all, every coffee and doughnut shop this side of the canal. Tony wasn’t selling. That place in Chatham….”

“Nuts 4 DoNuts,” the fat man cut in.

“Yuh, that place,” I said. “The Antonios put in a lot of work to make that place what it is.”

“One of the best, for sure,” the fat man said. “Right up there with the Depot.”

“And the sports book out of there?” I said.

“I wouldn’t know about that.”

“Someone said it was thriving, maybe second only to the Depot on the entire Cape,” I said, making it up.

“Your someone doesn’t necessarily have all the facts.”

“So help me out,” I said.

“The cops were his best customers,” he said. “Who among Chatham’s finest would bust the guy who makes the best doughnuts, assuming there was bookmaking going on in the back room, which I don’t know there was.”

“Kind of a business model?” I said. “Doughnuts in front, sports book in back?”

“If you say so,” the fat man said.

“I heard how Tony was behind the counter when this guy came into the shop and got in line and waited ten minutes before he got to the front. He asked for a raspberry jelly doughnut, which he loved and coveted. And Tony looked up at the guy and snatched the last three raspberry-filled from the display case for himself. I heard he told the guy, sorry, we just ran out. I heard that Tony knew they were this particular customer’s favorite…and then Tony got whacked, right then and there, in the shop, behind the display case.”

“You heard wrong.”

“Didn’t Fat Tony Antonio have a wife and kids?” I said.

“Never asked him.”

“Slammin’ Sammy Saperstein,” I went on. “What a guy…a credit to the industry. Now that was obviously a hit…smack in the middle of the forehead. Don’t you think?”

“Whoever did it was crazy,” the fat man said. “Thank Mother Mary and Jesus that I’m out of that game.”

“So, Plaid Petey,” I said. “What kind of beef did the boys have with him?”

The fat man shrugged his shoulders. “No problem,” he said. “Just that the world’s a better place without him. Simple as that. Ask anybody.”

“So you did the Cape a favor?” I said.

“Not just the Cape,” he said. “Greater Boston, the whole Bay State, all New England.”

“What’s one hit when the whole world’s a better place now that Petey’s gone, right?”

“Right.”

“So, except for Petey, which was basically a humanitarian gesture, you’ve never been a hit man at all?” I said.

“How’d you guess?”

########

Bruce Kauffman was a longtime North County Times editor and writer with emphasis on business and sports. He now operates a writing consultancy and authors creative works. This is is from his latest effort, a work in progress, exclusively at The Grapevine. For more visit Oce

Be the first to comment on "Tale of the Toppled Hurler: A Peter Hartwell Story (Part 11)"