In the San Pasqual Valley southeast of Escondido, in the darkness of early morning on December 6, 1846, the American Army under Stephen Watts Kearny fought the bloodiest encounter to win California from Mexico. The San Pasqual battle was only one of the military encounters in California in the war, but proved to be the bloodiest and most controversial as to outcome. San Pasqual Battlefield State Historic Park is at 15808 San Pasqual Valley Road. For more information, visit sandiego.org.

San Pasqual Battleground State Historic Park/Russel Ray

San Diego Historical Landmarks—#12: San Pasqual Battlefield Site

When I first became interested in history at the age of 11, it was all about wars—Civil War, World War I, World War II, and the Vietnam War, which had taken my youngest uncle away from our home. I found the Civil War, the 20-year period leading up to it, and the 20 years afterwards, by far the most interesting.

My interest in the period from about 1840 to 1885 has never wavered. Thus, San Diego’s Historical Landmark #12, the San Pasqual Battlefield Site, and the San Pasqual Battlefield State Historic Park, really piqued my interest.

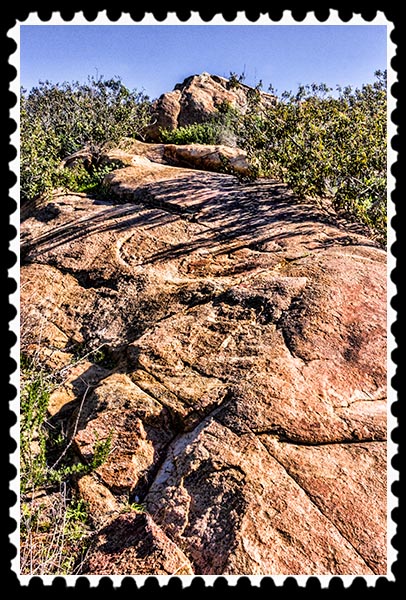

For thousands of years, the Kumeyaay ancestors of the San Pasqual Band of Mission Indians lived in the area. Many sites throughout the valleys and mountains were of religious and historical importance to them, featured in oral legends and stories. There still are remnants of the Indians’ activities in the San Pasqual Valley, such as small indentations, called cupules, in huge boulders:

Cupules are “rock art” produced by Kumeyaay Indians. The actual meaning of the cupules is not known although in some societies small indentations were used in various youth initiation and fertility ceremonies.

San Pasqual Valley is a large area just west of the Volcan Mountains. The valley always has served as a route into the San Diego area from points north and east, which made it valuable to both sides in the Mexican-American War. It also served as the road into San Diego County from the Southern Immigrant Trail, and from 1857 to 1860 it was part of the 125-mile stagecoach route for the San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line between the Carrizo Creek Station and San Diego.

The Battle of San Pasqual occurred December 6-7, 1846, as part of the Mexican–American War (1846–48). It was the first time that the U.S. Army engaged in an extended war in a foreign land, and was instrumental in shaping the geographical boundaries of the United States. At its conclusion, the U.S. added over one million square miles of territory, including what today are the states of Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas, as well as portions of Colorado, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming.

The battle was the bloodiest of the Mexican-American war. General Stephen W. Kearny’s “Army of the West”—140 American soldiers— engaged a small contingent of Mexican Californios and their Presidial Lancers Los Galgos (“The Greyhounds”), led by Major Andrés Pico.

The Army of the West had left Fort Leavenworth in what is now Kansas in June 1846. Their trek to California to help conquer it for the United States took them through the southern desert where they faced lack of water and lack of food for both them and their mounts.

The Mexican forces had lances which proved much more effective in close battle than the shorts swords of the Americans. American forces were also at a disadvantage because the gunpowder for their rifles was damp from the previous cold, rainy night.

Painting of the battle:

After 167 years, who won the battle still is disputed. Both sides claimed victory, the Americans by holding the battlefield and the Mexicans by inflicting greater casualties. Eighteen American soldiers were killed in the battle with three others dying later of their wounds. One soldier was missing in action. The Mexican leader, Major Andres Pico, reported that only one Mexican was killed, a figure that still is disputed by Americans.

Each side achieved its objective of the battle, the Americans claiming territory and the Mexicans disabling an enemy force. History, though, generally concedes victory here to the Mexicans. The Americans began the battle as the aggressors but by the end, they had been immobilized by the Mexicans, who then held the initiative. Of course, while the Mexicans won the battle, the Americans won the war.

The Visitor Center is high up on the hillside:

The gentleman at the Visitor Center on Saturday, January 24, was a joy to talk with. I spent about 30 minutes with him discussing the battle and some of the historical figures involved in the battle, such as General Kearny—Kearny’s name is widespread throughout San Diego County—and the already-famous Kit Carson—San Diego County’s second-largest municipal park is named after Kit Carson and is just a few miles away.

A “mountain howitzer” is on display just outside the entrance to the Visitor Center:

The mountain howitzer was adopted in 1836 by the American government for use on the frontier. As a lightweight cannon of 500 pounds on 38-inch wheels, it could be quickly and easily assembled and disassembled, and could be transported on pack mules using a specially designed saddle. It could be removed from a mule, assembled, loaded, and fired in under a minute! The mountain howitzer on display used an 8-ounce powder charge to project a shell 900 yards.

Pack mules could carry up to 300 pounds a distance of 20 miles a day on a mountain trail. However, they can pull about seven times more weight than they can carry, so the mountain howitzer was designed to have shafts attached to it to allow it to easily be pulled by a mule.

There are two trails in the park, one a quarter-mile nature trail with markers identifying native vegetation and with expansive views of the park and valley below….

….and the other being a one-mile round trip to Battlefield Historical Monument….

If you are not inclined for a hike, or don’t have time, you can drive to the monument site and park, which is what I did.

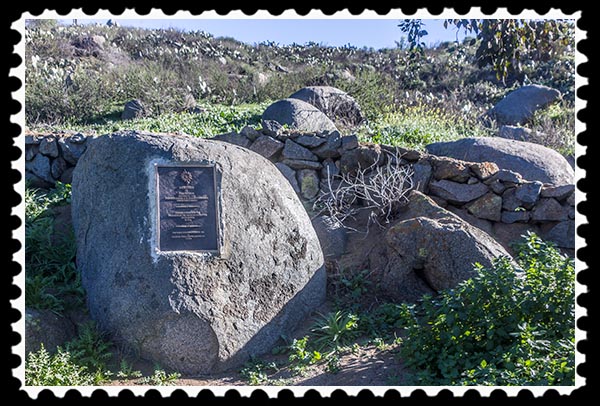

Sadly, the bronze plaque on the largest monument had been unceremoniously stolen during the height of the Great Recession, probably taken to a recycling center and sold for scrap….

Apparently the plaque had on it the names of American soldiers, but I couldn’t find out if it had all of the names or just the names of those killed in action. There are plans to replace the plaque, but not with bronze….. plastic this time, colored to look like bronze.

There is another bronze plaque a distance away from, and not seen from, the main monument boulder, which probably is what resulted in its bronze plaque not being stolen.

Most of the San Pasqual Valley is now part of the San Pasqual Valley Agricultural Preserve, home to citrus, avocado, and dairy farms, as well as the San Pasqual Valley American Viticultural Area. American Viticultural Areas are defined by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau of the United States Department of the Treasury.

That sounded serious!

Since I had no idea what a Viticultural Area was, I went to Wikipedia and found that it is a region that grows wine grapes. Wow! The government is involved in regulating areas that grow grapes for wine. I’ll just leave it at that….

The Visitor Center is open only on Saturdays and Sundays from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Temperatures can get extraordinarily hot (often in triple digits!) during summer days, so prepare appropriately with a good supply of water and outerwear to protect you from the sun.

Also located within the park boundaries is the San Diego Archaeological Center and the San Pasqual Indian Cemetery. I did not have time to visit them during this trip but you know I will, with my handy dandy Canon camera in tow!

For more information about Ray’s property inspection service and blog, visit Real Estate Solutions by Russel Ray at http://russelray.com/. Or call (619) 341-0173.