Big Tepee? Do you know the way, Jose’?

Go around Escondido. Ask anyone about the Big Tepee. Since we can’t bet dollars against donuts anymore — some donuts cost much more than a dollar — let’s wager dollars against Chargers super bowl appearances that people asked that question will believe you should go to a big tepee of the medical kind.

There’s an answer to the madness, however.

Just as people think of Seattle when they go Space Tower, New York and Times Square, New Orleans and Bourbon Street; Escondido once had a distinctive community landmark as well.

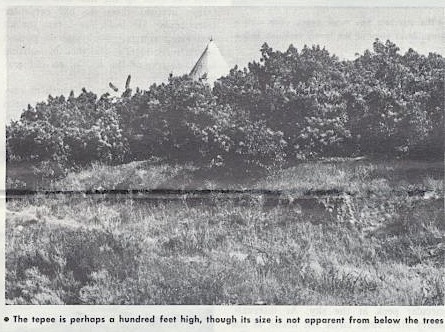

We’re talking Big Tepee. It was a defining civic wonder for all the world to see. Pilots used it as a navigational marker. Drivers on the road from Temecula to San Diego used it as a landmark. It could be seen for miles around, no joke.

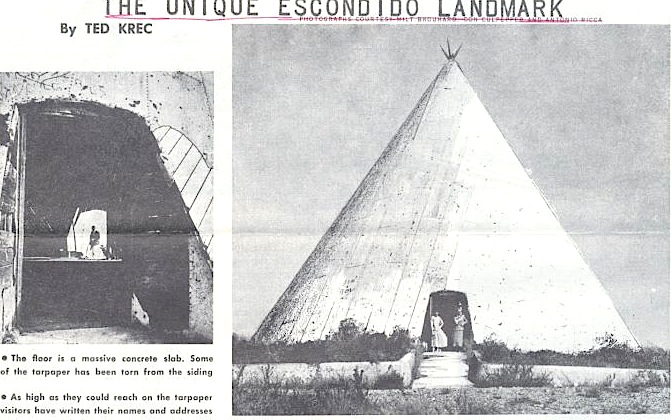

“The unique Escondido landmark” as it was called in a 1957 article by Ted Krec in AAA’s Westways magazine was built in 1929 by A.L. “Abram” Houghtelin, a 60-year-old retired Idaho rancher.

For some reason, Houghtelin built the 50-foot-high, 60-foot-wide Big Tepee on a 960-foot hill at the vicinity of Summit and San Pasqual Valley roads in South Escondido near what is now the San Diego Zoo Safari Park.

But why?

We don’t say why lightly.

Over the years, even past Houghtelin’s 1956 death, with one of his sons in charge, nobody ever got a straight answer as to why he built the tepee or what, if anything, he planned to do with it. Additionally, origin stories and Big Tepee references from other sources assumed mythic proportions, kind of like a Donald Trump stump speech or King Arthur.

“It IS a tepee,” a reckoning Krec said. “But who built it? And why was it built? Those were questions I, too, asked the first time I saw it; but it took a dozen trips to Escondido and a lot of interviews to uncover the real story.”

Krec got some crazy answers when he asked around town. One story was an Oklahoma oil millionaire built it to house his Native American wife who was homesick. She died and he just walked away, leaving the tepee on the hill.

Another story was that an eccentric miner who had struck gold erected it as a monument to his “faithful Indian guide.” Yet another tall as a Big Tepee tale was it marked the spot where a powerful Indian chief once dwelled.

For the record, Houghtelin bought the land, terraced the hilltop with retaining walls topped by concrete slabs and, oh, by the way, planted avocado and citrus trees. The wooden forms, by press accounts, used to mold the concrete went into construction of the tepee.

After that, good luck getting a straight answer. At various times, Houghtelin and sons suggested it was intended for a residence, a guest lodge or an attraction enticing real estate investors to the area.

Whatever it was going to be

Wham bam, thank you 1920s Republican fiscal policies, The Great Depression rendered all points moot. Houghtelin, and his son John, returned to Idaho. Another son, Clair Houghtelin, stayed hard-by the Escondido ranch taking care of business.

All this is not to say that the Big Tepee went unused. It became an sanctioned, and sometimes unsanctioned, people’s party place with groups of one to many finding their way up the dirt and unimproved roads, across the hilltop to what resembled, by all accounts, a ghost town, or at least a wigwam of the spirits.

A party thrown at the site by college students Connie Johnson and Murray Ehmke in 1939 made it into the San Diego Union and the Escondido newspaper. “Li’l Abner” was the theme with decor including livestock — don’t ask — willow tree cuttings, and featuring a live orchestra.

Civil defense spotters used the tepee during World War II, just in case, you know, Escondido got Pearl Harbored. Boy Scout troops and YMCA members used it for meetings. Even the Escondido Historical Society got into the act using the tepee for gatherings. Hayrides happened. Fundraisers.

While the Houghtelin family continued owning the property, and gave permission for the official gatherings, young’uns often snuck onto the grounds to do their time-honored things. “All of our boyfriends would take us up to the tepee,” one longtime Escondido resident said.

Going got tough

It was all good to go through the mid-1960s when vandalism, like hair styles and a little something called Vietnam, got out of control. Trespassing masses trampled crops and sensibilities. Clair Houghtelin finally pulled the plug in 1976, blocking off the driveway leading to the structure.

Clair Houghtelin had other wig-wham concerns. “It isn’t safe for visitors to go up there,” he said to an Escondido newspaper in May, 1977. “Boards tear off it, and it might even topple in a high wind.”

That’s exactly what happened six months later. Strong Santa Ana winds toppled the tepee on Dec. 20, 1977.

Big Tepee was no more.

History doesn’t stop there, however. The property was sold in the 1990s. Property disputes led to a murder with a teenager who was partying at the scene accused of killing a man who lived nearby. The property was gated, and frankly, tepee-less, forgotten.

Now, Paul Harvey reference, for the rest of the story

Not being able to resist a tall tale of such a momentous type, yours truly went in search of the Big Tepee, or at least it’s site. Interestingly enough, especially since I didn’t even see Krec’s 1957 article until later, my experiences echoed his quite closely.

That sucker was hard to spot. Following Summit Drive from the farm stand at San Pasqual Valley Road, it was exceedingly difficult to figure out where the heck that tepee once resided.

Pulling into Hungry Hawk Winery and Vineyards on Summit Drive, a tremendous place by the way highly recommended, Ed Embly, owner of the family-based business, laughed. Perhaps the only one who remembers, he pointed due north.

Obviously. That’s where Big Tepee once stood.

Seeing and believing being two separate items, the road to the tepee continued in a historically disheveled fashion. Rather surprisingly, up Summit Road a piece and to the left, a small family tepee stood out in a large yard. Turned out to be a totally unintentional homage to the much larger tepee with which the family was blissfully unaware. They just liked to camp outside, it was said.

Or maybe there’s just something in the air there that cries for to the big wigwam to the stars. We’ll never know or tell.

Finally, arriving at a point near where it must have been, the trusty vehicle made it to the top of a small dirt path that must have led to the sacred place should it not have stopped in its dirt tracks.

Giant no trespassing signs and farm fields to the summit led one to surmise. That’s just the way it goes sometimes, end of story, for now.